Hidden

A Cryptic Estate

For centuries, buildings and towns were built layer upon layer. Churches were built on the foundations of temples, and cathedrals over churches, taller and grander; the crypts of cathedrals were often what remained of the previous church. Today, however, we are more respectful and reverential of those buildings that have survived the ravages of rapid urbanisation. We tend to ‘heritage list’ such buildings to preserve them, and we do not build over or in front of them. That said, additions are often necessary to ensure an historic building’s compatibility with our modern lifestyles, and so we seek to disguise these additions, by placing them to the rear, or in the case of this grand home, hiding them below ground level.

Constructed in 1889, this home was designed by Walter Liberty Vernon, who was a highly influential architect of the time, and who counted both the Art Gallery of New South Wales, located in The Domain, and Sydney’s Central Station among his many projects. Along with these grand public works, he also designed many private residences, including Family Heritage, which Luigi Rosselli Architects recently had the privilege of updating.

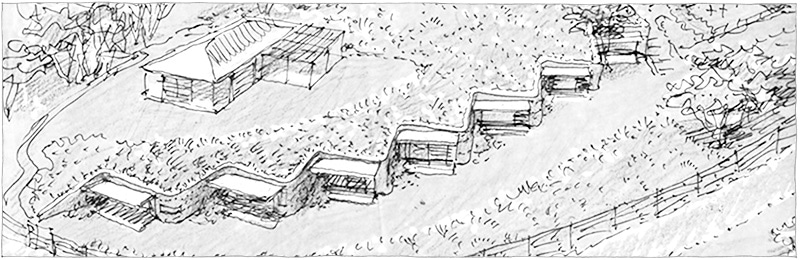

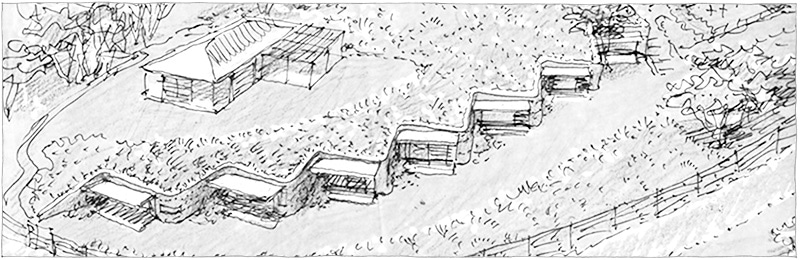

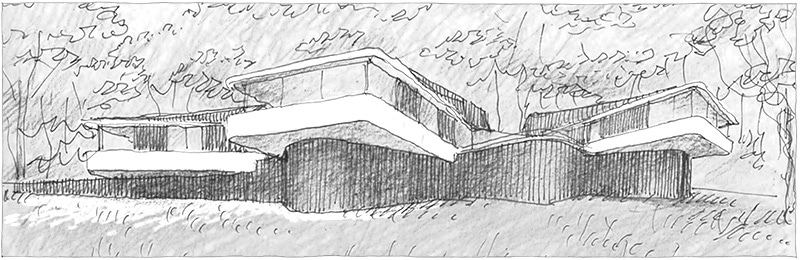

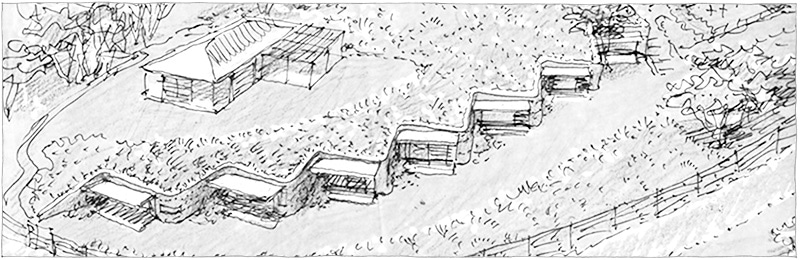

Built for a successful accountant, the original two-storey dwelling stood tall on a large parcel of land blessed with views down to Sydney harbour and the city of Sydney opposite. In considering the design for the new additions, there was a requirement to retain what remained of the garden after a significant portion of the original plot was sold off in the 1990s for a development of townhouses. To achieve this aim, the solution was to demolish a more recent garage addition, and replace it with a new wing that covers four levels, including subterranean spaces and a roof garden akin to an iceberg tip, which occupies the space where the ‘upper’ garden of the property used to be. Housed within the upper level of the additions are a new kitchen, dining and sitting room; a contemporary space that complements a modern lifestyle, enhanced by easy access to the light and airy garden space. The lower levels contain a wine cellar, and all the apparatus: a gym, massage room, sauna, spa, swimming pool, necessary for achieving immortality. Along with the more mundane elements to support that aim, such as the plant room, and a water tank for the pool.

Borrowing from both the Latin and Greek words for hidden, ‘cryptic-architecture’ is not a new concept, though it is one that may be put to effective use where the aim is to preserve what already exists, or to make effective use of limited space. World renowned examples of ‘cryptic-architecture’ include, Chinese-American architect, I.M. Pei’s pyramid addition to the Paris Louvre; Fabrica, the addition integrated into the confines of a seventeenth century Venetian villa by Japanese architect, Tadao Ando for United Colors of Benetton; and the wonderful underground buildings of Emilio Ambasaz.

Authorities within Australia are quite opposed to utilising cryptic-architecture as a solution to the challenges of our crowded urban landscape, preferring instead to allow ever growing rates of land clearance and poorly resourced urban sprawl. Supposedly the objections are formed on the basis of reducing the volumes of landfill, and noise pollution resulting from excavation, yet those same authorities show none of those same concerns when approving large scale public works such as vast underground road systems. North Sydney Council is one of the few authorities to support this type of solution. Geographically located on Sydney’s lower north shore, the topology of the Council area is characterised by the steep slopes of a rock shelf, and it allows for the placement of swimming pools, and utilitarian elements such as garages, plant rooms, and water tanks, out of sight below ground to retain a leafy ground plane.

The gardens of Hidden are a lush interpretation of the Victorian affection for lawn and edges, blended with subtropical planting artfully and personally selected by William Dangar of Dangar Barin Smith.

Interior designer, Romaine Alwill combined her collection of modernist and classic interior elements within the late-Victorian interiors of the house. With his design, Vernon was in a transition phase from the ornate and layered Victorian clutter, to the purer approach of the Queen Anne period, and Romaine was the right person to pick up on this subtle change.

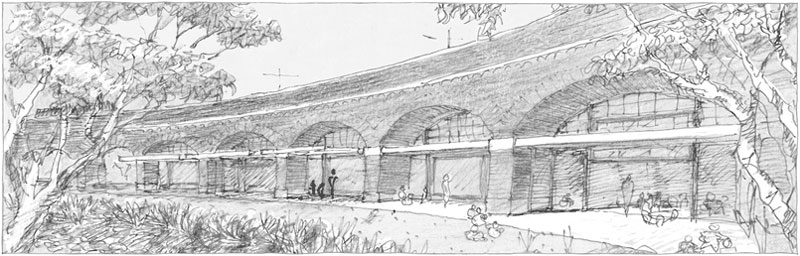

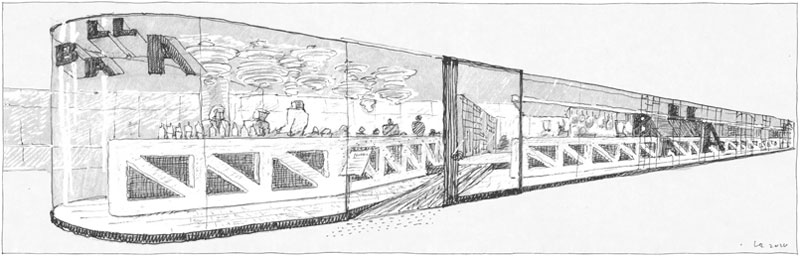

Luigi Rosselli Architects’ design for the subterranean swimming pool drew inspiration from the cryptic nature of the place. Excavated from the sandstone rock ledges that characterise large areas of Sydney’s lower north shore, the pool had to speak the language of the stonemasonry. While clearly architecturally striking, the parabolic arches also happen to be the most structurally efficient shape capable of carrying the load of the multiple levels situated above the pool. Skylights cut into the floors of the two levels above the pool draw light down into the space and foster a sense of connection to the world beyond.

Council: North Sydney Council

Design Architect: Luigi Rosselli

Project Architect: Evan Howard

Interior Designer: Romaine Alwill for Atelier Alwill

Landscape Architect: Will Dangar for Dangar Barin Smith

Builder: Pimas Gale

Joinery: Correlli Joinery

Heritage Constultant: John Oultram

Structural Engineer: Phil O’Hara for Northrop Consulting Engineers

Swimming Pool Stonemasonry: Chris French for French Stonemasonry

Custom Skylight: Tilt Industrial Design

Geothermal System: CWL Group

Stucco Veneziano: Mark Stanford

Marble Slabs: Granite Marble Works

Brass Hardware: Savage Design

Photography: Prue Ruscoe

Drone Photography: Piers Haskard

© Prue Ruscoe

© Prue Ruscoe

© Prue Ruscoe

© Prue Ruscoe

© Prue Ruscoe

© Prue Ruscoe

© Prue Ruscoe

© Prue Ruscoe

© Prue Ruscoe

© Prue Ruscoe

© Prue Ruscoe

© Prue Ruscoe

© Prue Ruscoe

© Prue Ruscoe

© Prue Ruscoe

© Prue Ruscoe

© Prue Ruscoe

© Prue Ruscoe

© Prue Ruscoe

© Prue Ruscoe

© Prue Ruscoe

© Prue Ruscoe

© Prue Ruscoe

© Prue Ruscoe

© Prue Ruscoe

© Prue Ruscoe

© Prue Ruscoe

© Prue Ruscoe

© Prue Ruscoe

© Prue Ruscoe

© Prue Ruscoe

© Prue Ruscoe

© Prue Ruscoe

© Prue Ruscoe

© Prue Ruscoe

© Prue Ruscoe

© Prue Ruscoe

© Prue Ruscoe

© Prue Ruscoe

© Prue Ruscoe

© Prue Ruscoe

© Prue Ruscoe

© Prue Ruscoe

© Prue Ruscoe

© Prue Ruscoe

© Prue Ruscoe